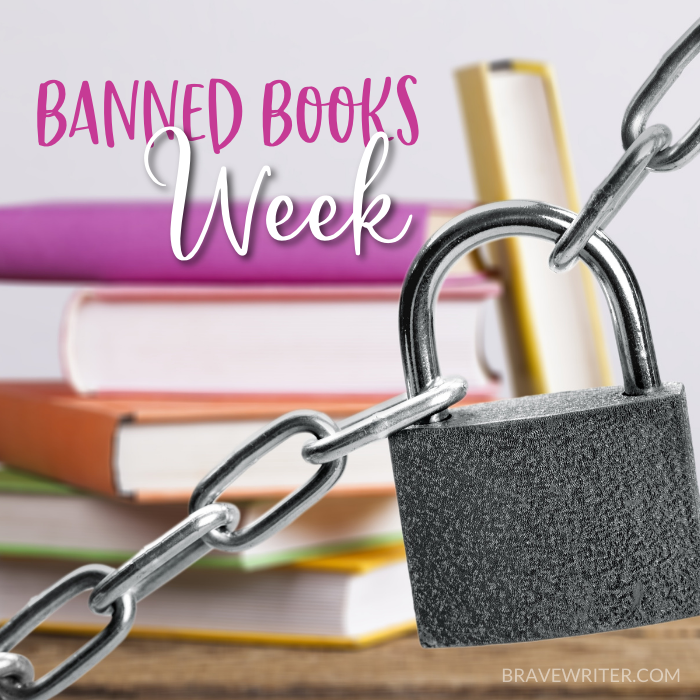

Banned Books Week is an annual opportunity to celebrate the freedom to read. This special week shines a bright light on attempts—both recent and long ago—to censor books.

If this year’s event passed you by, no worries. It’s never too late to dive into this canon. You can pick up a banned book and start reading it today!

You might wonder, why would I want to pick up a banned book? And why, especially, would I want to share a banned book with my kids—and use it to study grammar, punctuation, and literary devices?

We hear you. And we have thoughts to share.

What is a banned book?

The American Library Association (ALA) makes a distinction between challenged and banned books:

“A challenge is an attempt to remove or restrict materials, based upon the objections of a person or group. A banning is the removal of those materials. Challenges do not simply involve a person expressing a point of view; rather, they are an attempt to remove material from the curriculum or library, thereby restricting the access of others. As such, they are a threat to freedom of speech and choice.”

Raising awareness of banned books helps ensure readers an ongoing opportunity to engage freely with diverse ideas and perspectives. At Brave Writer we celebrate that intellectual freedom as a means to promote new empathy and deeper understanding. This is why we make it a point to carry mechanics and literature singles for challenged or banned books!

Digging for Treasure

At first, it might feel counterintuitive to seek out banned titles. After all, we aim to give our kids the best literary experiences we can, poring over carefully curated reading lists to find those “must-read gems” all the experts are raving about. How surprising it is to discover then that the treasures we seek work overtime, often appearing on both the “classics-you-can’t-afford-to-miss-lists” and the banned books lists too!

To name just a few, think:

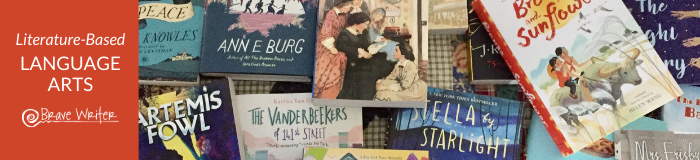

If you’ve been with Brave Writer for a while, you may recognize that these titles are featured in a Dart, Arrow, or Boomerang. These books were selected for our language arts program because of their:

- exquisite writing,

- honest representation, and

- timeless relevance.

Presented at the right time, in the right context, these tales have the power to enrich family culture and conversation in wildly meaningful ways. Let’s explore how!

Relevancy Makes Readers

Books get banned for a wide range of reasons, but one element these titles usually share is authors with a willingness to take on the hard stuff. Banned books don’t shy away from the subjects kids are thinking about. Relatable stories of familial challenges, peer pressure, bullying, prejudice, loss, and grief gift our kids with road maps to hold onto when they’re feeling lost or overwhelmed. Books can make it easier to digest and process the feelings these topics give life to. And have you noticed that relatable books turn kids into readers?

Books as Mirrors and Windows

Many books deemed “controversial” are great teachers of empathy and self-awareness. Education reformer Charlotte Mason taught that books give children a chance to learn about the wider world. Educator Emily Style took this thinking a step further coining the expression “books as mirrors and windows.”

- Mirrors are those stories that reflect a child’s identity and their environment back to them. The impact of seeing one’s life reflected in stories is significant because it’s a signal to kids that their lives matter and that there are other people who think and feel the same way they do. What a good feeling that is!

- Windows are stories that offer a view of someone else’s experiences and help children see the humanity in others. These stories often reveal surprising commonalities that transcend our differences and may explore issues such as ethnicity, disability, gender orientation, and religion. Diving into complex stories alongside well-crafted characters is a chance to step outside of comfort zones to learn about others. Banned books show the world as the big and sometimes confusing place that it is while providing exposure that cultivates empathy and resilience in readers.

Banned books spark Big Juicy Conversations!

Do you think the topics covered in Charlotte’s Web are too sad for children?

Who could this story help?

Do these themes belong in a kids’ book?

Why?

Why not?

Think how delicious this conversation might be served up with cookies and milk! Substantive stories stir up controversy, and controversy is fodder for juicy conversations. Open-ended discussion of questions like the examples above helps develop critical thinking skills. If given opportunities to engage regularly in rich conversation, kids will grow the skills they need to thoughtfully discern and distill their beliefs and values.

You Get to Decide

Books that stretch our thinking, make us evaluate and consider the world from a series of vantage points, are doing their job. How fortunate we are to have access to them.

Not every banned book deserves a place on your bookshelf, of course. You get to decide what deserves a place in your collection. But that’s the whole point. You decide.

Mark your calendars. Next year’s Banned Books Week begins Saturday, September 24, 2022. As the date draws closer, keep an eye on your library’s calendar to see what events are planned and join the fun with your family. Of course, there’s no need to wait till next year— you can pick up a conversation starter today!

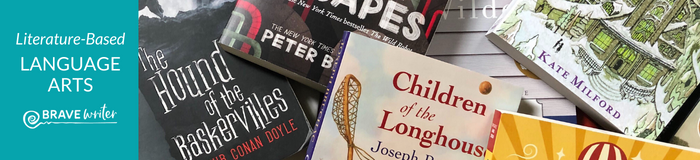

Banned Book Literature Singles at Brave Writer:

Dart Titles

- Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White

- The House at Pooh Corner by A.A. Milne

Arrow Titles

- Amal Unbound by Aisha Saeed

- Artemis Fowl by Eoin Colfer

- The Bad Beginning by Lemony Snicket

- Because of Winn Dixie by Kate DiCamillo

- From the Mixed Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler by E. L. Konigsburg

- Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh

- Journey to Jo’burg by Beverley Naidoo

- Leon Garfield’s Shakespeare Stories: William Shakespeare’s work has been banned throughout history—this book is a worthy distillation of the Bard’s famous works.

Boomerang Titles

- Anne of Green Gables by L. M. Montgomery (Communist Poland)

- The Call of the Wild by Jack London

- The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer

- Catching Fire by Suzanne Collins

- Cry the Beloved Country by Alan Paton

- The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

- Divergent by Veronica Roth

- Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

- The Fault in Our Stars by John Green

- Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes

- The Giver by Lois Lowry

- The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams

- The Hobbit by J. R. R. Tolkien

- The Hound of the Baskervilles by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

- The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros

- The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

- I Am Malala by Malala Yousafzai and Christina Lamb

- The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan

- Life of Pi by Yann Martel

- A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith

- A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle

Slingshot Titles

- The Secret Life of Bees by Sue Monk Kidd

- Animal Farm by George Orwell (coming soon)

- I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou (coming soon)

- The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald (coming soon)

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg! See if you can spot other banned books on our Literature Singles list. There are more!