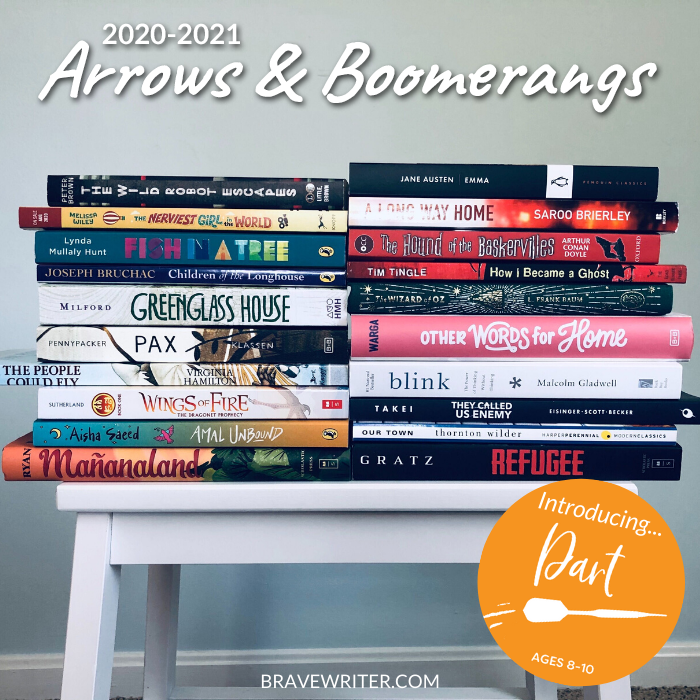

Brave Writer launched their new book lists for the coming year. It’s an annual celebration of reading and learning. Children tune in to our webinar with their parents and eat special breakfasts all for a glimpse of the joys of reading books they’ll share with their families during the coming school year.

I look forward to this day every year. I read a brief description of the book on camera to tease it and the families guess which book in the comments section until I finally reveal it with a flourish.

We’re committed in Brave Writer to providing a diversity of authors and protagonists, genres and stories. It matters to me that we give our families a variety of perspectives to consider each year. It takes us an astounding amount of time to vet books and find the right mix for each level (30 books total).

What is usually the high point of the Brave Writer calendar (what we affectionately call the “NFL Draft of books”) felt different the day of the reveal.

I knew that in the wake of the unjust murder of George Floyd, my social media feed would be flooded with outrage, with calls to action. Minneapolis were on fire and riot police were out in force in Los Angeles and Denver and Memphis.

I’m sensitive to the conversation, want to do my part to advance the cause of anti-racism in America.

As I prepared over breakfast, I realized that the best work all of us can do is with our children. The breakfast table is where we learn what to believe.

I took a class in graduate school that examined the civil rights movement in America. I’ll never forget my professor explaining that the dinner table conversations for African American families were different from those held at suburban white dinner tables.

For instance, in Los Angeles, during the 1980s and 1990s, it was well known in South Central that the police sometimes planted evidence to make an arrest of a black man. This understanding was as well established in their families as my understanding that if I were to be pulled over by a cop for a traffic ticket, I would be treated with respect and could probably get out of it if I cried.

When the OJ Simpson trial ended in a “not guilty” verdict, many people cited the acquittal of the police in the Rodney King case—that this was a revenge verdict. But that’s not what the jurors said. When asked on what grounds they found OJ not guilty, I remember one juror saying, “The LAPD planted the evidence.”

I thought at the time how unlikely and ludicrous that was—how could anyone think that the LAPD would be corrupt?

And then the late 1990s brought us the Rampart Scandal.

“More than 70 police officers either assigned to or associated with the Rampart CRASH unit were implicated in some form of misconduct, making it one of the most widespread cases of documented police corruption in U.S. history, responsible for a long list of offenses including unprovoked shootings, unprovoked beatings, planting of false evidence, stealing and dealing narcotics, bank robbery, perjury, and the covering up of evidence of these activities.” (Wikipedia)

It was years later in grad school that I remember the shock it was to discover that the police-planting-evidence report the juror cited had been believable to her, because those cases were well known in South Central. She had heard them for years.

(This is not a comment on whether the police did or did not plant evidence in the OJ case—only that Johnny Cochran’s claim that they had had more weight for this juror as a result of the well established understanding that the LAPD did sometimes plant evidence.)

As it turns out: table conversations determine so much of what we believe to be true.

Which is why I’m committed to reading diverse literature with children—to having breakfast, lunch, and dinner conversations that include other experiences of life in America, and in the world than our own.

If all we know is what we hear at home, it’s hard to accept someone else’s report. But if we go out of our way to encounter the stories and experiences of others, deliberately choosing to be uncomfortable for the sake of greater awareness and understanding, we are more likely to grow a wiser, more just society.

As I logged into Zoom and plugged in my mic, I imagined children all over the world meeting protagonists from Pakistan and Syria. I imagined them talking about a harrowing journey to freedom in Mañanaland. I thought about the power of African American folk tales and George Takei’s autobiographical experience in the Japanese internment camps portrayed in his graphic novel. This years’ students will read two books about Native Americans by Native Americans and another book about being Chinese American by Grace Lin.

Our beliefs are shaped by the stories we trade with our families. One way to combat racism of all types is to read better books, to care about the characters, to learn their perspectives, and then talk about them together.

A good practice for adults too.