The professor-archetype

Have you ever noticed that in some children’s literature, a professorial type male character is often included as a father-like figure to a gaggle of kids? He might even be the father.

Have you ever noticed that in some children’s literature, a professorial type male character is often included as a father-like figure to a gaggle of kids? He might even be the father.

This man is usually interesting to the reader because he seems oblivious to typical parental worries—he doesn’t throw up red flags of caution when the children experiment with dangerous tools, contraptions, or potions. He is unworried by their retellings of journeys into magical worlds or forests. He is non-plussed by their cheeky philosophy or their impolitely expressed opinions. He often accepts their fantastical tales with aplomb, barely registering alarm when they return from adventures riddled with danger, and shows a surprising capacity to believe the stories at face value.

This man-character doesn’t lecture children and sometimes, infuriatingly, doesn’t even give advice or warnings when they seem most merited. He, himself, might be engaged in his own mysterious doings and ponderings, which leave the children bewildered and impressed.

I think of characters like Professor Dumbledore (Harry Potter), Professor Kirke (Chronicles of Narnia), Professor Martin Penderwick (professor of botany, The Penderwicks), Merlin (The Sword and the Stone), Wayne Szalinski (Honey, I Shrunk the Kids), Gandalf (Lord of the Rings series) and even the benign homesteading pioneer, Pa Ingalls (Little House series).

This archetype is an intriguing figure. Children gravitate to these men and I’ve been curious about why. I have a few hunches. It seems to me that children crave the experience of being taken seriously. They want their words to be weighed by adults and then found to be full of truth, sincerity, and importance. Even if children’s ideas or experiences could be explained away by an adult’s greater worldliness, children still hope to find in the adult they respect, an appreciation for the way they know the world so far.

These professor-like men uniformly respect a child’s grasp of the world they live in and they are appropriately engaged in their own battles and explorations so as not to be overly impressed by the children’s, either. These men’s lives are independent of whether or not the kids turn out, survive, or discover the same truths the professor-types take for granted.

Additionally, the professor-archetype believes he doesn’t know everything and is open to learning from any source, including the naive experiences of kids. This openness registers deeply with readers. It gives child-readers hope that the thoughts and feelings they have about the life they are living can find a kind, sympathetic, or at minimum, respectful audience in the adults they love and trust.

When I get worked up (wanting to cover all the bases, trying to protect my children from danger – even my adult children!, lecturing them from the vast-expanse of my more abundant failures and successes, disbelieving their reports because they don’t match what I’ve known to be true), I sometimes envision Professor Kirke and his wave-of-the-hand type attitude. He couldn’t be bothered explaining away Lucy’s experience of Narnia. If she reported it and she was trustworthy and we admit that there are things in the universe we do not yet know, there must be truth in Lucy’s report. End of story.

A profound respect for the truthfulness of children. Impressive.

When faced with my children’s inexperience and their youthful impulses, I have to resist the temptation to be a stodgy, know-it-all adult who fails to see magic and opportunity in a child’s point of view. I have to sometimes sit on my hands (which tend to do all the talking, lecturing, and waving) and let the perspective “ride”—let it run its course or express itself without restraint to hear the full-bodied nature of what it wants to say. I have to make room for what makes me uncomfortable.

I’m learning how to let risk be a part of a child’s (or young adult’s) exploration. I’m trying to hang back, talk less, and listen more. I want to be open, quieter, more curious, less case-closed.

I want to relate to my kids, believing that life is a better teacher than a lecture.

I want to respect their experiences without being a busybody about them.

It’s funny. This professor-archetype character is so popular with kids. They just love the surprise of an authority figure who would treat children as peers and invite them into real danger trusting them to their competencies, heart (valor), and goodwill—at least on the level of how they express their participation in the world around them, and how they understand their part in it.

These men (and women) make good role models for us. Don’t you think? Who are your favorite adults in children’s (or any) literature? What have you learned from them? I’m curious.

Cross-posted on facebook.

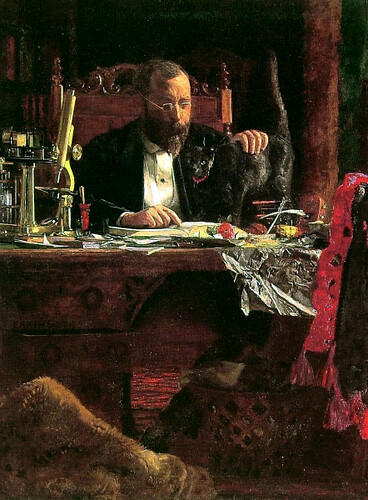

Image Portrait of Professor Benjamin H Rand by Thomas Eakins (1874)

I married a man who is like this! He is unflappable. 🙂 Our boys get to do things that other boys only dream of doing. Right now, they are all up on our roof put new shingles down. Our youngest is eight and the envy of all the neighborhood boys.

After I originally left a comment I seem to have clicked the -Notify

me when new comments are added- checkbox and now each time a

comment is added I get 4 emails with the exact same comment.

Perhaps there is a means you can remove me from that service?

Kudos!

You really make it appear really easy along with your presentation but I in finding this matter to be really something that I believe I’d never understand. It kind of feels too complex and extremely broad for me. I am having a look forward to your next post, I will try to get the grasp of it!

This web site truly has all of the information and facts I needed about this subject and didn’t know who to ask.